On the day after Christmas last year (2013) my daughter-in-law Dorothy came up from our guest house where she and my son Alex stay when visiting me with an odd-looking book in her hand asking where it had come from. It was different in format from most standard books, on heavy drawing paper and had a plastic spiral binding, giving it an almost “home-made” appearance. It was the cover that caught my attention. I looked at it for a few seconds and then my head began to swim.

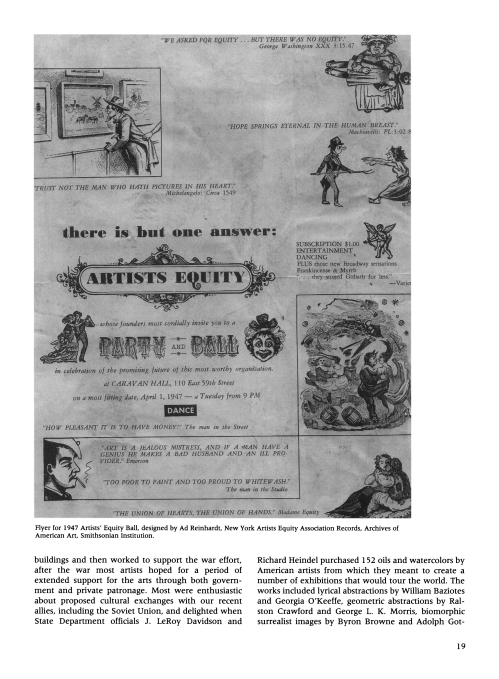

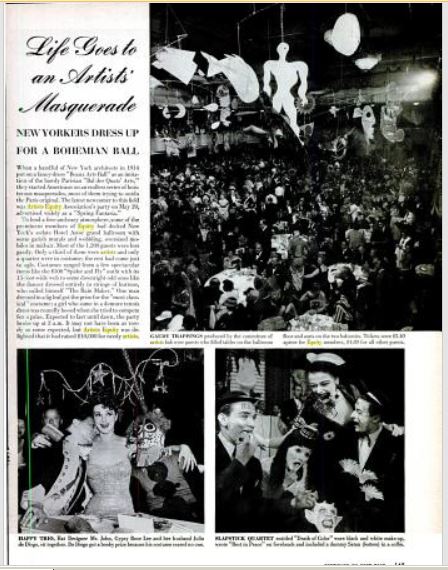

To understand my confused reaction take a look at my earlier post entitled “Gypsy de Diego”, a humorous anecdote about how Gypsy Rose Lee called herself “Mrs Julio de Diego” when calling my mother, Agnes Kovach, and “Gypsy Rose Lee” when calling my father, Alexander Kovach, at his engineering office. In that post there was this sentence: “For the first couple of years of their existence Artists Equity threw a huge, wild New Year’s Eve costume party in the old Manhattan Opera House.” The cover of the book reveals three mistakes in that one short line. Look at the date, May 4, 1951. Artists Equity was formed in April of 1947, more than a couple of years before; May 4 is not New Year’s Eve and the Hotel Astor was not the old Manhattan Opera House. (Nor was it the Waldorf Astoria. See the story of the hotel and Times Square in Wikipedia.)

The cover and the book are fraught with significance for the history of mid-twentieth century American art. The rest of this post is devoted to revealing some of that history from my very personal perspective. Often, when I do research in subjects like this, I find myself wandering down unforeseen byways which turn out to be as interesting as the original subject. Often the research brings back to memory names and events that were clouded over by time and confused by later events. I will report on all of these as they turn up.

The first question then is what is this book? Is it the one I described in the Gypsy de Diego post?

The first page after the cover states that this is volume II of Improvisations and that the first volume was conceived and created the year before, 1950, and that two thousand copies of this edition were printed. A stamp, in red, at the bottom of the page reads “290”. A few pages in I found this:

(These prints were created by directly etching zinc plates for lithograph masters which would only hold up for about two thousand impressions. It is not possible to correct errors in such a circumstance which explains the tip of the nose and lower lip on the left side. Later you will see quite a number of these permanent mishaps.)

Was this the page I recalled in the Gypsy post? It cannot be. I remembered it as an ad for Klieglights paid by my father’s friend and business associate, Herbert Kliegl, and that must be correct because why else would Gypsy Rose Lee, editor of the AGVA (American Guild of Variety Artists) Newsletter have called inquiring about how to contact whoever paid for the ad? Klieglights was then (and, I think, still is) one of the major suppliers of theatrical and motion picture lighting. No, this is not the advertisement that I was thinking of. (The question of who paid for this page kept nagging me as I thought was it Kliegl again or someone else? Then one of those dim memories brightened. I think my father paid for it just so my mother would have the opportunity to do another page for the second year.) Incidentally, I think the Klieglights ad was also of classical statuary, a full figure of Mercury with winged feet and so on.

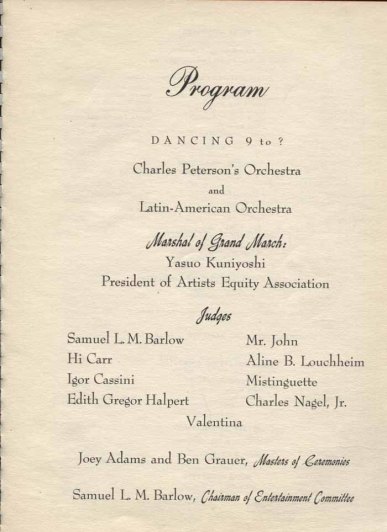

Then there’s the matter of the Marshall of the Grand March at the end of the ball which was a key aspect of the Gypsy de Diego post. This is the fifth page of Improvisations II:

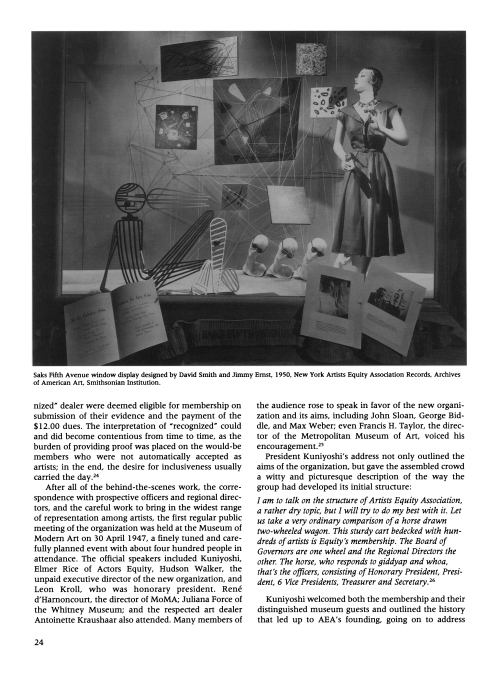

Note that the Marshal was AEA President Yasuo Kuniyoshi (not Gypsy Rose Lee and Julio de Diego) who was near the end of his final year as president. The by-laws set term limits at two terms of two years, maximum. Kuniyoshi , the founder, became president at the creation of the organization in April of 1947. (Mr. John was a celebrity designer of women’s hats; Aline Loucheim was an art critic for the New York Times; Igor Cassini was a gossip columnist for the Hearst newspapers; Edith Halpert was the owner of the Downtown Gallery, the cradle of American modern art; Mistinguette, French chanteuse, age 75 at the time, was once the highest paid female entertainer in the world; Valentina was a top women’s fashion designer.)

So, Improvisations II is definitely not the book I was remembering. Now the question is, was Improvisations I what I remembered? So far, all the evidence of the first volume I found is the cover (in Amazon) and two of the advertisements, one by Reginald Marsh and the other by Max Beckmann:

(I have to take a liberty with the narrative sequence for an amusing story. I was present at the AEA reception for Beckmann at the Plaza Hotel in 1947 when Beckmann first arrived in the US. It appeared that he had very little English and as he shook hands with each well-wisher passing along the reception line all he said was “Thank you, thank you”. While I was watching this repeated ritual a “Park Avenue matron” with a fey looking young man in tow shook hands and then insisted on a conversation. She told Beckmann that her son had just finished his degree at ‘Hahvud’ and wanted to know what he should do next, study in Paris or one of the American Art Institutes, another university, etc., etc. Beckmann, looking puzzled, just kept saying “Thank you, thank you”.

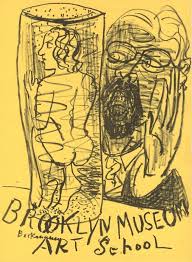

Incidentally, at the time he did this ad for Improvisations he was teaching at the Brooklyn Museum Art School. He died about seven months later, in December of 1950.)

One of the problems I had in confirming that the 1950 ball was the one I was seeking was my memory of my own chronology. When I wrote the Gypsy de Diego piece I was thinking it occurred in the mid-forties, before I went to the University of Chicago in the fall of 1946. Of course when I found out that the AEA was started in 1947 everything was in doubt. Then I remembered that I had dropped out of college in March of 1950 and returned home to New York. Now I could start searching for any historical documentation, especially of the early days of the AEA. The major find was an excellent 1999 paper by professor David. M Sokol then teaching art history at the University of Illinois Chicago, “The Founding of the Artists Equity Association After World War II”. I found my ignorance of what was going on with the New York arts community, my mother’s school, the Art Students League and her teacher, Yasuo Kuniyoshi, was both broad and deep. Of course, as I expected, along the way I stumbled into all sorts of related matters, had a number of memories revived or revivified and any number of misunderstandings corrected. The Sokol paper is so rich that I have appended it (and a thumbnail biography) to this post and will be quoting from it often.

Proof of the 1950 Date

After a great deal of hit-and-miss searching I came across the June 12, 1950 issue of Life Magazine which used to finish each issue with an article about some sort of festivity such as cotillions, weddings, parades and so on. This issue had a masquerade ball.

That’s the first edition of Fleur Fenton Cowles chi-chi magazine Flair dated May 1950. The next page had this text:

and on the rest of the page we have

and on the rest of the page we have

with the picture on the lower left being:

with the picture on the lower left being:

Q.E.D. The ball I attended was the Spring Fantasia of 1950 and the book was Improvisations I.

Kuniyoshi, Artists Equity, Woodstock and So On

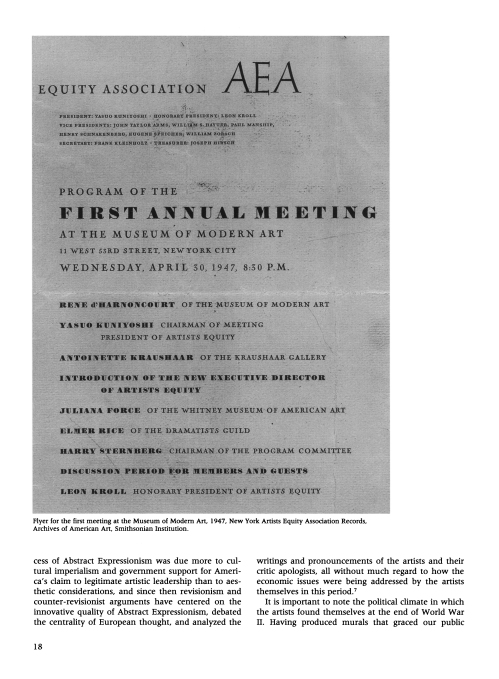

My mother was never a “joiner”, never part of any organization for any purpose. Since she was a student of Kuniyoshi’s at the time of its founding, she must have been among the very first members of the Artists Equity Association but she barely mentioned it to me. When I heard that Kuniyoshi was elected its first president I assumed it was largely an honorary position, that he was selected as a gesture of respect by the artists of New York or the US. So, for sixty-seven years I had it all wrong. Read what David Sokol has to say on the subject: “The guiding genius and founder of Artists Equity was Yasuo Kuniyoshi … Galvanized by the modest prospects for artists after the end of the federal art projects and the loss of opportunities for artists with the end of the wartime economy, and feeling that government hostility to the arts made the renewal of any kind of federal art project unlikely, he met during the latter half of 1946 with like-minded friends and created both a new organization and a new approach that would bring artists together to work on behalf of their economic well-being.” “New approach” may have been the central idea which I will discuss later.

Not long after the above statement in Sokol’s paper this photograph is included:

The markup of the photograph on the upper left side is this:

Which says: “Artists Equity/ Testimonial Dinner to/ Yasuo Kuniyoshi/ in Honor of his Retrospective/ Show at the Whitney Museum/ Cafe Montparnasse March 25, 1948” It really was more than that. This was the first time the Whitney granted a living artist a retrospective. Prior to this they only showed lifelong retrospectives of deceased artists or, if living, groups of artists. There may have been some political aspects to the Whitney’s decision to present this show, a quiet defiance of the forces that killed the “Advancing American Art” exhibition.

Now look at the bottom left corner of the photograph:

The man on the left is my father, Alexander J. Kovach, and facing him (second woman from the bottom) is my mother, Agnes Kovach. Here is the attribution line above the picture:

which says the photograph is from the Mitzi Gallant Papers in the Archives of American Art at the Smithsonian. The AEA turned over its archives to the Smithsonian some time ago.

Mitzi Gallant was in Kuniyoshi’s class along with my mother. When I think of Mitzi I have a single distinct association: laughter. She was a “good time girl” I guess. She must have been “well fixed” living in the Essex House on Central Park South (not too shabby). I may have been in her apartment once because I get a distinct image of a single thick semicircular archway separating the (possibly sunken) living room from the entry hall. (The Essex House had a huge neon sign on the roof with the “Essex” above the “House”. One night the first two letters of the top word blacked out. This was still considered a thigh-slapper twenty years later.)

Another “well fixed” classmate was Vivian de Pinna whose grandfather established the very elegant department store on Fifth Avenue and 52nd street. She was just about sixty at the time (and lived until 95) and thus seemed rather grandmotherly to me. I have one distinct memory of her taking us out to lunch (Schraft’s?). I see from the web that she painted abstractions for years and they are frequently featured in current auctions.

While I am off on this tangent I’ll add one other classmate, a woman who lived in her aunt’s house in Princeton, making the ninety minute commute by rail every day, whose name I cannot remember (first name may have been Ruth). The aunt was a retired Institute for Advanced Study archeologist. Her neighbor was Albert Einstein. After The Bomb was dropped Einstein received huge amounts of mail every day, so much that the post office made a daily special delivery run to his house only, from people seeking advice and counsel for all sorts of problems, marital, financial, what-have-you from the smartest man in the world. One morning Einstein appeared in the aunt’s doorway holding a large basket filled with envelopes and said, “Why are they doing this? Who do they think I am? A Jewish John J. Anthony?” (For those too young to remember him, John J. Anthony had a very popular personal advice radio show, rather like a radio version of Dear Abby.)

In Sokol’s paper not long after the banquet photograph the following passage appears: “Many conversations that led up to the founding of AEA took place in the summer and early fall of 1946 in Woodstock, New York. Kuniyoshi was one of a large number of artists who either lived full-time in or around Woodstock or spent their summers there (as he did). These men and women were the people with whom he shared his ideas about an organization that would address the pressing economic issues they all faced; not surprisingly, large numbers of Woodstock artists were active in the early years of the association.”

According to all reports by other Woodstockers, Yas (pronounced “Yahss”) Kuniyoshi had a very nice house overlooking the Ashokan Reservoir, with a large screened-in porch ideally suited to late afternoon gatherings and cocktails. I never was invited there and did not see it myself. (While on the subject of what I actually witnessed, I should point out that I only met Kuniyoshi once, at the 1950 ball and that the scene played out something like this: Agnes Kovach: “This is my son.” Kuniyoshi: “How do you do?” Roger: “How do you do?” – the end.) There was a large gathering there on many an evening all summer long with a lot of the AEA’s and Art Students League’s business discussed.

The League had a branch in Woodstock which was headed, in spirit and, I believe, administratively, by Arnold Blanch who taught one of their classes. Blanch also figured largely in the Artists Equity Association’s Woodstock outpost (and, consequently, in AEA in toto). The League was a very big attraction during the summer months. Blanch, who worked on several WPA projects, was married to Doris Lee, who also taught a course, who created several major works under the WPA Federal Arts Project, most notably for the US Treasury Dept. and the Central Post Office in Washington, DC which were held in high esteem (almost equal to Anton Refregier’s Rincon Annex post office murals in San Francisco, which I will discuss later). She went on to have a renowned and varied career. In 1963 and ’64 both Blanch and Lee were recorded for an oral history project. Lee’s statement came close to home for me and some other posts in this blog: “One day in 1935, (I was still quite young), the same day I received word that I’d won the Logan Prize at the Chicago Art Institute and also that I had won the commission to do murals from the Treasury Department in Washington. It was really very staggering to me, and very exciting. I had a studio, (while I always had a house here in Woodstock) that I went to in New York in the winters at 30 East 14th St. Kenneth Hayes Miller was there, Alec Brook, Emil Ganso and a great many other painters had studios there. And it was a good thing I had this very large studio because that was where I did the Treasury Department Murals.”

Now I had an address for the studio building I called the “Janice studios” in my earlier post about my mother’s studio, Bob Barrell and the parties with so many interesting people we had there. Using the address and Google Earth I found the image of the building which apart from the store on the ground floor, appears to be unchanged from the early 1940s.

I think the second floor front studio, the most desirable in the place with the fewest stairs to climb, huge space and lots of north light, was Kenneth Hayes Miller’s. I think Kuniyoshi had the one above and that other second and third floor tenants included Raphael Soyer, Reginald Marsh and several other well known names dating back to the ’20s. I think Yas tipped my mother to the availability of her fifth floor rear place when Nahum Tschacbasov gave up his teaching position at the League. It was the least desirable studio, five exhausting flights up, not much bigger than a broom closet with one dirty window facing south.

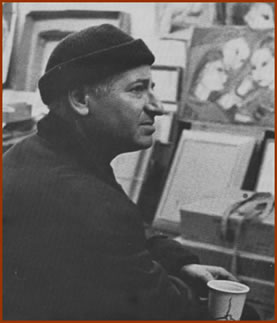

Kuniyoshi in his studio, looking north across 14th street. The painting is “Upside down Table and Mask”

Far and away the most popular social gathering place, Kuniyoshi’s porch, the League or the AEA notwithstanding, was Deanie’s restaurant, particularly the ample outdoor dining area. It seemed as though each summer new little cliques would form based, obviously, mostly on who was there at the time and they mostly gathered at Deanie’s (and at the bars, I would guess). As one consequence each summer my mother would have some one or two people she spent spare time with. One such was Paul Burlin, in 1948 I think, who was one of the more urbane people I have met, very witty and with comments on everyone and everything that could etch glass. Another constant lunch companion in the summer of 1950 was Eugene O’Neill jr, who was not an artist but a respected professor of Greek at Yale, most known for “The Complete Greek Drama” an anthology of English translations done with Whitney Oates that is a standard to this day. In September he committed suicide in the manner of Seneca, sitting in a warm bath and slitting his left ankle and wrist.

Joe Presser was a constant, being one of the longest standing Woodstockers and Janice studios tenant where he and his wife, Agnes Hart, illegally lived like Bob Barrell (the studios were only to be used for work, not dwelling) so we saw him very often in New York. Joe always had a small drawing pad in his left hand and sketched incessantly, sometimes seeming like he wasn’t even looking at what his hand was drawing. He also did strange mixed media paintings, mixing watercolor, oil, gouache even pastels and crayons on paper. Of course, often the oil or gouache would start peeling off in a matter of weeks. I think he was an excellent draftsman and often created rather impressive pieces. About fifteen years ago someone told me that years before Joe had committed suicide by jumping off one of the over-the-Seine bridges. (This will be my last morbid note – promise.) His work was shown recently at the Fletcher Gallery in Woodstock and there’s an excellent website at josefpresser.org

There were two Woodstock “regulars” who stand out in my memory for being disliked by many. First was Karl Fortess who was despised by Kuniyoshi’s students and loyalists for openly playing the part of a fawning sycophant with Yas, presumably with a view to gaining a teaching appointment at the League. If that was his intention, in the end he succeeded. It would seem Fortess was obsessed with the lack of financial success but that certainly wasn’t unusual at that time, with the end of the WPA, as Professor Sokol pointed out. It was, in fact, a major part of Kuniyoshi’s motive in establishing Artists Equity. There is a video of Fortess talking on this and related matters on YouTube.

Yas and Fortess – Judging from Yas’ graying this must have been taken in 1952 or 1953 the year he died.

The other was Hermann Cherry who was characterized as a sort of Uriah Heep. I have almost no memory of him except how much he was despised. He may have been rather short… I do recall him approaching Deanie’s outdoor cafe and hearing people say “Oh no. Here comes Cherry”. Also I never heard him called by his first name, just “Cherry”.

Another very popular social activity was going to the Friday evening movies shown in the town hall. One showing that drew a lot of attention had a short documentary along with the feature that showed an artist with his canvas lying flat on a garage floor, splashing whole cans of wall paint and squishing tubes of oil paint directly onto the canvas. There was a great deal of laughing, hooting and howling.

There was a good Actors Equity rated summer stock theater – I don’t know whether it was an Equity “A” company though. I don’t think many of the artists were in its audiences – it mostly appealed to tourists. One summer Lillian Gish was featured for several weeks. I saw her a number of times at or walking near Deanie’s. She wore a silk-like (rayon?) slack suit with a color halfway between beige and pink and even though she was near sixty years old at the time, would get wolf whistles from the passing truckers.

Back to the Book

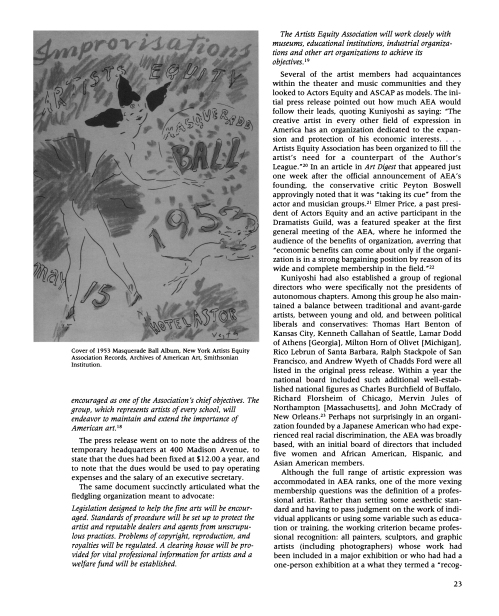

Take another look at the cover for Improvisations II:

Now look at the artist’s signature in the upper left corner:

Anton Refregier was one of the best and most widely known names at the time. In 1941 the WPA-FAP granted him the largest project they had ever assigned, valued at $26,000, a twenty-seven panel mural depicting the history of California for the WPA-built Rincon Annex, the central post office for the city of San Francisco. The timing of the award was unfortunate, coming just before our involvement in WW II. The Rincon Annex was the funnel to most of the mail going to our Pacific forces making it much too busy to allow Refregier to paint his murals. The work was interrupted until 1945 and proceeded slowly thereafter as each panel was challenged by one or more interest groups, Refregier trying to accommodate nearly all of them by making changes, until it was finally completed in 1948. Throughout there were charges of radical left or communist propaganda in the murals for such things as siding with the unions in the general strike and so on. (The same complaints were made about the murals in Coit Tower which date to the same era, where such sympathies were more evident. In the late seventies my wife and I became friends with Langley and Blanche Howard who were still fairly radical. Langley painted the Coit mural “Industry” but was more widely known at the time we knew him for his many magazine covers for Scientific American. Appended to the end of this post is a note I wrote for a local newsletter on the Howards time in Bolinas. After years of attempts to have the murals destroyed they have just been painstakingly and expensively restored.) There is a very good summary of the travails of Refregier and his murals by Rob Spoor in the San Francisco City Guides site which can be seen here.

During the Depression in the mid-30s a large number of front rank artists were affiliated with a variety of leftist organizations. In the arts the two most prominent were the American Artists Congress and the Artists Union. Kuniyoshi was a founding member and vice president of the Congress which was a Popular Front organization but I have a hard time believing he was much interested in the politics. (Popular Front was the name given to outfits that were affiliations of liberals and leftist radicals, especially communists, often partly for some common purpose such as fighting the rise of European fascism. The Artists Congress supported the Loyalists in the Spanish Civil War, for example.) The other popular artists organization was the Artists Union which affiliated itself with the rising industrial and crafts unions, joining them in strikes and protests. I don’t think either of these organizations were very effective in improving the economic lot of artists – but they were still around, very much alive during the WPA years which was part of the reason right wing congressman were so eager to destroy WPA murals. A central point in Kuniyoshi’s “new approach” was the avoidance of any outside affiliations whatsoever, especially political connections.

The prevalence of leftist thinking led to widespread similarities in stylistic matters that I used to call the “WPA style”. It was very prevalent in the New York Worlds Fair of 1939/40 in Flushing (which I went to every summer day of both years) . One example would be the “worker hero” a laborer in a sleeveless t-shirt with a hard hat on and bulging biceps. A very similar figure was everywhere in Soviet art. I was first exposed to this model even before the Worlds Fair in a painting by my mother. She was taking lessons, mostly life classes, in a WPA course conducted by Bender Mark. At the end of one semester he assigned a project to create a large painting on the student’s own subject. My mother’s project was unusual in several ways. First was the “canvas” which was burlap, stretched over a frame made with Mark’s help at the Main Street studio and sized with glue. Second was the size: it was very large, something like four by six feet. Third was the medium, poster paints, made from the powders and applied fairly dry and thick. Last was the subject, three or four worker heroes (hard hats, sleeveless t-shirts, bulging biceps) digging a tunnel with the tunnel boring machine (mole) face in the middle right background as the focal point. The mole face was quite accurately represented. (The background to all of this was that my father at that time was an electrical design engineer for the NY Board of Transportation and was involved in some of the expansions to the Independent System subway then underway. He, no doubt provided descriptions of tunnel digging and the mole. He told me many years later that he had worked on the design of the Second Avenue line which was never started.)

In 1946 two U. S. State Department officials bought 152 paintings, oil and watercolor, by modern American artists, broke them into a couple of smaller groups and packaged them to be touring art exhibitions called “Advancing American Art” for circulation in Europe, Latin America and elsewhere to show that there was a robust American art movement and that was not derivative from Paris or other European sources. The shows were actually opened in a few venues and were very well received even though the American press, especially the Hearst chain and Look Magazine, was relentlessly attacking them as being subversive, communist and so on. Several pre-McCarthyite congressmen joined in the assault but it took no less than Harry S. Truman’s condemnation to bring the whole venture to a close. (I find the irony in the similarity of Josef Stalin’s and Truman’s taste in art to be rather depressing.) The paintings were auctioned off. David Sokol has a good, more detailed account of this sordid affair in his paper which you really should read. This episode must have thrown a real scare into the American art community, presaging as it did, continuing hostility from the government, killing any prospect for further WPA-like support with continuing hard times in the outlook. Kuniyoshi, in particular, must have taken the message to heart.

Kuniyoshi was also represented in the show with this 1924 painting:

Note the use of heavy, pure black for shades and shadows. Kuniyoshi went through several distinct eras in style and substance until he arrived at those he evidenced at the time my mother entered his class. At that time his paintings looked like these:

At this time he was experimenting with under-painting, using black instead of the sienas and umbers used by Dutch renaissance masters. (Students of other teachers at the League used to tease Yas’ students saying he was doing charcoal drawings in oil.). Here’s another example:

This the painting on the easel in the studio photograph included earlier in this post. Note the treatment of the cloth and mask. At the time the book turned up, this student effort by my mother also emerged. It had been very badly handled, off the stretcher and folded in four – but the hand of the master is still visible:

Contents of the Book

To view a larger picture click on the thumbnail. This also allows viewing in slideshow mode.

After these images there are links to further information about the better known artists.

Links to further information about the artists

Anton Refregier: Rob Spoor on the murals; Biography.

Joseph Hirsch: Wikipedia biography.

Harry Sternberg: Wikipedia biography.

George L. K. Morris: Biography.

Betty Kathe: Auction records only.

Agnes Kovach: Amazon, eBay listings only.

Georges Schreiber: Biography.

Robert Gwathmey: Wikipedia biography.

Hans Hoffman: Wikipedia biography.

Leon Kroll: Wikipedia biography.

Gerrit Hondius: Gallery publicity.

Robert Delson: Auction records only.

T. Lux Feininger: Wikipedia biography.

Gladys Rockmore Davis: Wikipedia biography.

Louis Bosa: Michener Museum.

Stuyvesant van Veen: NYT obituary.

Isabel Bishop: Wikipedia biography.

Helen Ratkai: Auction records only.

Adolf Dehn: Wikipedia biography.

Julio de Diego: Wikipedia biography.

Sidney Simon: NYT obituary.

Amy Jones: Auction records only.

Lewis Daniel: Penn Academy catalog.

Chaim Gross: Wikipedia biography.

Eric Isenburger: Isenburger collection.

Fletcher Martin: Wikipedia biography.

Lee Jackson: NYT obituary.

Antonio Frasconi: Wikipedia biography.

Dorothy Block:Wikipedia biography.

Lena Gurr: Smithsonian archive.

Samuel Adler: Wikipedia stub.

Leonard Lionni: NYT obituary.

George Biddle: Wikipedia biography.

Ann Leboy: Auction records.

George S. Ratkai: Auction records only.

Nicolai Cikovski: Spanierman gallery biography.

Henry Varnum Poor: Wikipedia biography.

Reginald Marsh: Wikipedia biography.

Elias Newman: NYT obituary.

Harry Gottlieb: Wikipedia biography.

Raphael Soyer: Wikipedia biography.

Lilian MacKendrick: CS Monitor interview.

Max Weber: Wikipedia biography.

Milton Avery: Wikipedia biography.

Gwen Lux: Wikipedia biography.

Mitchell Siporin: Wikipedia biography.

Marcel Vertes: Commercial site.

Ben Shahn: Wikipedia biography.

Flash Memory (item published in a local newsletter called “Hearsay News”)

Over the past couple of months I have been working off and on (mostly off) on a new post for my blog about the founding of the Artists Equity Association, its founder and first president, and my mother’s teacher, Yasuo Kuniyoshi and the art scene in Greenwich Village and Woodstock circa 1950.

The name “Anton Refregier” figures slightly at the beginning of my story. Refregier, working under a Work Progress Administration – Federal Art Project grant, created the murals for the Rincon Annex post office in San Francisco which have been considered the finest public art in California by some. The subject is the history of California. It is huge: twenty-seven panels totaling four hundred square feet. The painting was done from 1941 to 1948 with a long hiatus because of The War.

The subject of communist sympathies comes up in connection with this work as it does in many another WPA – FAP project. There are sympathetic portrayals of such things as the San Francisco waterfront strike and other leftist social issues; in 1953 a McCarthyite congressman tried to have the murals destroyed and so on. For the most part Refregier simply shrugged off such allegations and the associated threats.

The same sort of accusations and disputes arose much more intensely in the case of the murals in Coit Tower which are just now the object of a very big and expensive total restoration (which will be open to the public in a few weeks). For those reasons I looked up the Wikipedia article on the Coit murals and what I saw made my eyebrows head for my hairline.

The creator of the mural titled Industry was John Langley Howard.

Langley and Blanche Howard rented a house on the Little Mesa in the late ‘70s. Barbara found Langley on one of the local beaches painting a landscape and brought him home to our house on Larch. (Barbara was forever bringing home her beach finds – we gained some very nice friends that way.) Over the next several months we became rather friendly, exchanging dinner invitations and the like.

They had lived a fascinating gypsy life. For example, they told us that they had lived a year in a tent on a beach outside of Brownsville, Texas, kids and all. There is an excellent obituary by Allan Temko for Langley available from SFGATE.com.

I either did not know or forgot about the Coit mural but I certainly did know about the many covers he did for his son who was the Artistic Director for Scientific American. Langley did about three covers a year and illustrations for articles in the magazine and if you ever saw them they would stand out in your memory as they have in mine. They were done in what I’d call a hyper-realistic style, not quite magic realistic – and they had an aura that lasts.

In less than a year Blanche came down with cancer and died rather soon thereafter. Langley moved on, perhaps to San Francisco, or Berkeley, or New York, or … He was in San Francisco, on Potrero Hill, when he died.

David M. Sokol’s paper

(A more readable PDF may be found here)